How to write a personal study introduction

- ABOUT THE THRESHOLD CONCEPTS

- THRESHOLD CONCEPT #1

- THRESHOLD CONCEPT #2

- THRESHOLD CONCEPT #3

- THRESHOLD CONCEPT #4

- THRESHOLD CONCEPT #5

- THRESHOLD CONCEPT #6

- THRESHOLD CONCEPT #7

- THRESHOLD CONCEPT #8

- THRESHOLD CONCEPT #9

- THRESHOLD CONCEPTS: A CRITICAL POINT

- THRESHOLD CONCEPTS: KS3 PROGRAMME

- TC1: MAKING MARKS - ON SURFACES, IN SPACE

- TC2: EXPRESSIVE APPROACHES

- TC3 : WORDS & ART

- TC4: EXPLORING (& ABUSING) ART HISTORIES >

- COUCH TO ARTIST: A 9-STEP PROGRAMME

- COUCH TO ARTIST: TASK 1 MARKS; WORDS

- COUCH TO ARTIST: TASK 2 VIBRATIONS; SENSATIONS

- COUCH TO ARTIST: TASK 3 TAKING SHAPE

- COUCH TO ARTIST: TASK 4 PUBLIC INTERVENTIONS

- COUCH TO ARTIST: TASK 5 PLAY, TIME

- COUCH TO ARTIST: TASK 6 HEAD, HANDS, HEART

- COUCH TO ARTIST: TASK 7 ART, WORDS; MEANINGS, CONTEXTS

- COUCH TO ARTIST: TASK 8 VALUES & MEASURES

- RED NOSE DAY DOODLE

- PRIMARY RESOURCES >

- INTRODUCTION

- PRIMARY: DADA WORKSHOP

- Superheroes! (And patterned pants)

- Robots!

- Ancient Greece: figures and forms

- Eek! A wolf ate my sketchbook

- Ancient Egypt: What a Relief!

- Shapes and (hi)stories

- Figures & Factories

- Alternative Art Histories

- LINES & LENSES

- STUFF & NONSENSE

- THE GRID - METHOD AND MISCHIEF

- Noughts & Crosses - playing with art (hi)stories

- THE ART OF INSTRUCTION

- PREHISTORY NOW

- Self-Portraits (Pt.1) About Face

- Self-Portraits (Pt.2) More than just a pretty face

- ABOUT THE THRESHOLD CONCEPTS

- THRESHOLD CONCEPT #1

- THRESHOLD CONCEPT #2

- THRESHOLD CONCEPT #3

- THRESHOLD CONCEPT #4

- THRESHOLD CONCEPT #5

- THRESHOLD CONCEPT #6

- THRESHOLD CONCEPT #7

- THRESHOLD CONCEPT #8

- THRESHOLD CONCEPT #9

- THRESHOLD CONCEPTS: A CRITICAL POINT

- THRESHOLD CONCEPTS: KS3 PROGRAMME

- TC1: MAKING MARKS - ON SURFACES, IN SPACE

- TC2: EXPRESSIVE APPROACHES

- TC3 : WORDS & ART

- TC4: EXPLORING (& ABUSING) ART HISTORIES >

- COUCH TO ARTIST: A 9-STEP PROGRAMME

- COUCH TO ARTIST: TASK 1 MARKS; WORDS

- COUCH TO ARTIST: TASK 2 VIBRATIONS; SENSATIONS

- COUCH TO ARTIST: TASK 3 TAKING SHAPE

- COUCH TO ARTIST: TASK 4 PUBLIC INTERVENTIONS

- COUCH TO ARTIST: TASK 5 PLAY, TIME

- COUCH TO ARTIST: TASK 6 HEAD, HANDS, HEART

- COUCH TO ARTIST: TASK 7 ART, WORDS; MEANINGS, CONTEXTS

- COUCH TO ARTIST: TASK 8 VALUES & MEASURES

- RED NOSE DAY DOODLE

- PRIMARY RESOURCES >

- INTRODUCTION

- PRIMARY: DADA WORKSHOP

- Superheroes! (And patterned pants)

- Robots!

- Ancient Greece: figures and forms

- Eek! A wolf ate my sketchbook

- Ancient Egypt: What a Relief!

- Shapes and (hi)stories

- Figures & Factories

- Alternative Art Histories

- LINES & LENSES

- STUFF & NONSENSE

- THE GRID - METHOD AND MISCHIEF

- Noughts & Crosses - playing with art (hi)stories

- THE ART OF INSTRUCTION

- PREHISTORY NOW

- Self-Portraits (Pt.1) About Face

- Self-Portraits (Pt.2) More than just a pretty face

WRITING ABOUT ART: PrepARING FOR THE PERSONAL STUDY

- To shed some light on what the Personal Study actually is (although the official line from Edexcel can be found here - other exam boards available).

- To provide students with practical advice for writing their essay - developing a theme, planning, structuring, writing a bibliography etc.

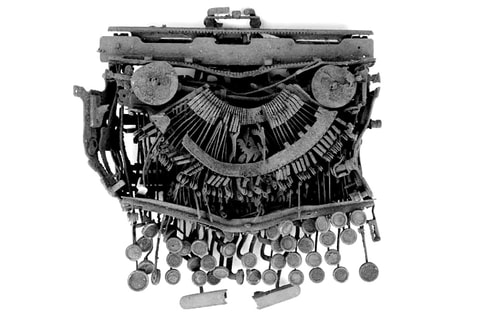

Typewriter Destruction, Jean Toche, 1966

- Try to write honestly and clearly, but not coldly. This is art not science.

- Read sentences aloud to hear how they flow - listen for the rhythm of your words.

- Vary sentence length. A longer sentence that cascades the reader forwards, gathering momentum as it snowballs along, will resonate most when followed by a sorter one. Honestly, it's true. This is also something to do with rhythm.

- When initially drafting your text, hit 'RETURN' at the end of each sentence. This obviously isn't appropriate for your final text, but in the drafting stage it can help you to see patterns in the flow of your writing.

- Do not underestimate the power of a full stop. A full stop provides an important pause. Good writing should not leave the reader exhausted.

- Avoid over-elaborating. Don't use three words if one does the job.

- Remember your writing is a gift to the reader. Don't waste their time, reward their interest. Insightful connections; reflective moments; imaginative metaphors; thought-provoking questions; a sense of purpose - these can all make for suitable rewards.

- Be no more than 3000 words (short and punchy is better than drawn out and draining).

- Focus on a specific artist/photographer or art movement (or alternatively, a concept or artifact).

- Be related to your own investigations and practical (course)work.

- Include supporting images - from your chosen focus, your own work, and relevant wider connections.

- Include a bibliography (see below).

- Be informative, insightful and provide a personal perspective.

- Be a well-presented labour of love; a pleasure for others to pick up and read.

Preparing for the Personal Study

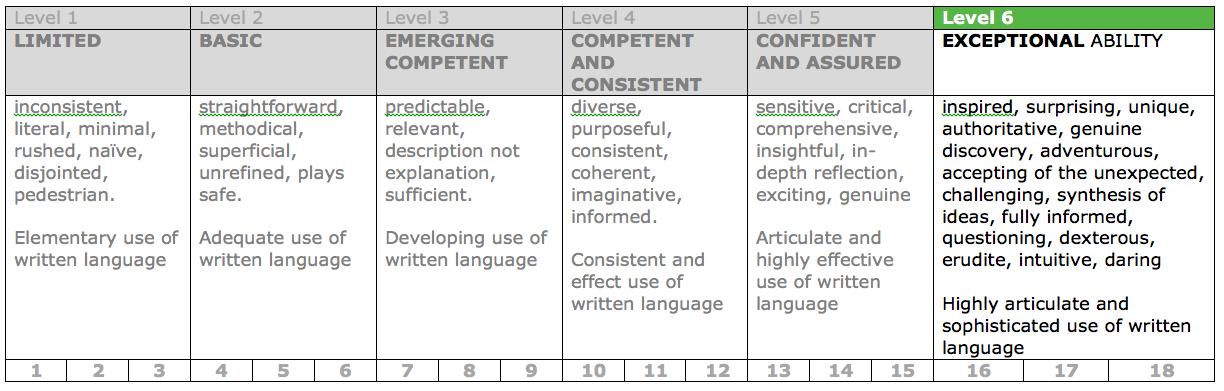

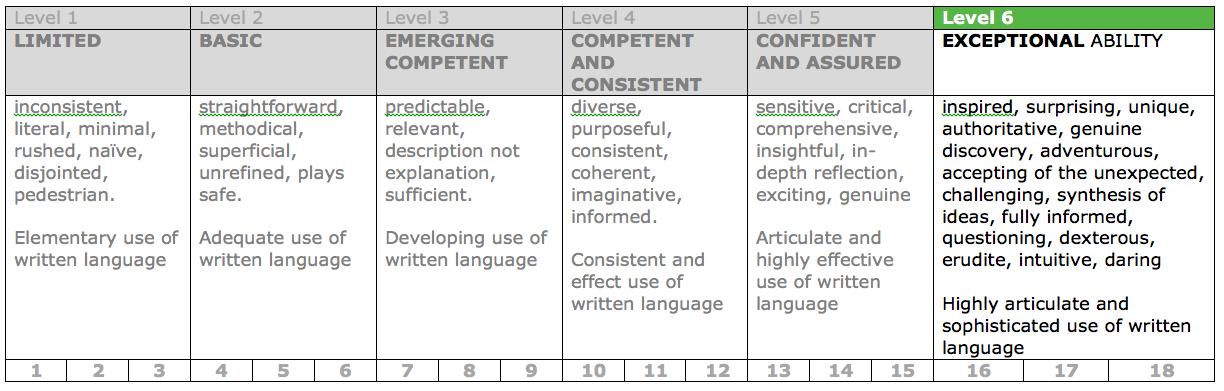

Obviously writing is a very different skill to, say, drawing, painting or declaring a urinal as art. But don’t underestimate the transferable skills in your creative locker. Being discerning, questioning, managing uncertainties, challenging expectations. These are all qualities that can help. And should you doubt their relevance, look below at the Personal Study descriptors for ‘Exceptional Ability’ (from Edexcel). These could equally describe an artwork.

But we are still dealing with words. Specifically, choosing the right ones and pinning them in the right place, and there is no quick fix for developing knowledge and literacy skills. However, there is something to be said for deliberate practice, and the Personal Study provides a great opportunity for this.

Getting started

Deciding which artist, art movement or theme to base your personal study on should not be a tricky decision. The Personal Study is related to your practical, personal investigations - your key themes and inspirations to date. Your sketchbooks and experiments should point you in the right direction. But it is okay to take a relevant sidestep and use the Personal Study as an excuse to learn more about a connected artist or theme (rather than following a line of enquiry you are already exhausted with).

- Liar! Jeff Wall, photography and truth

- Modernism, Abstraction and the work of Barbara Hepworth

- The Human Figure: Sizing up Euan Uglow

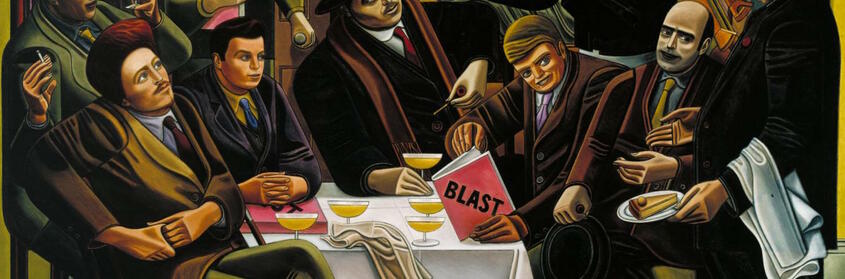

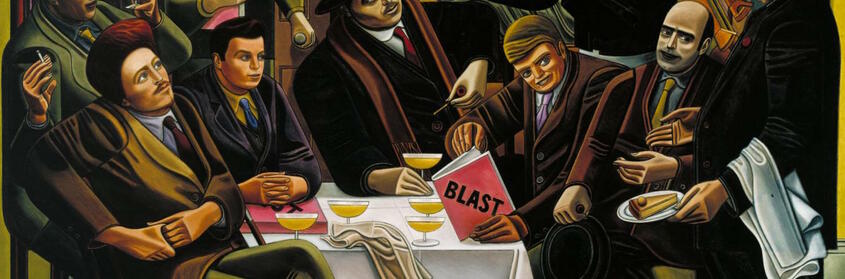

The Vorticists at the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel: Spring, 1915 (detail), William Roberts, 1961–2

Write an introduction that leaves the reader wanting to read more (but doesn't leave you wanting to write less)

Your introduction should tempt the reader in, but not at the cost of a whole week of your life shuffling around sentences. A common mistake is to throw a thesaurus at the opening paragraph until it resembles a download from artybollocks.com (yes, an actual website). Much better to start in a more straightforward way and simply get some initial thoughts down. The introduction can always be revisited and reshaped later, once you've found your writing mojo.

- Explain your interest in the subject and the connection that you have to this.

- Set out your intentions clearly.

- Provoke a desire to read on (for example, by using intriguing yet-to-be-answered questions).

- Reference relevant threshold concepts - the big ideas (or transformative knowledge) significant to your focus.

Regarding matters of tone, perhaps appropriate advice is this: Be yourself with your sentences, but be the very best version of yourself that you can be. Imagine yourself in super clear communication mode - informed, honest, reflective; bossing it.

Below are two examples of Personal Study introductions. The first is more straightforward, the second a little more elaborate:

INTRODUCTION EXAMPLE 1

I am fascinated with themes of identity. In particular I am interested in what 'identity' might mean to a portrait artist, and how they might set out to understand and capture a person's identity. Grayson Perry, contemporary artist, forms a main focus for this essay. His TV documentary "Who Are You?" has been a big influence on my work this year. After watching this series I found myself reflecting on how I might create a portrait that goes beyond simplistic observations to capture a stronger sense of identity.

INTRODUCTION EXAMPLE 2

There’s a common perception that a person’s identity is fixed - a fully-formed pearl found deep inside, resistant to change. But this perception strikes me as absurd. Identity is a far more complex, evolving matter. It can certainly be a struggle to determine one’s own personal identity, let alone identify or reveal someone else's. But this is a challenge every artist faces. Grayson Perry, in his TV documentary “Who Are You?” immersed himself into the lives of his subjects. His aim: to see through cracks of façade; to delve deeper beneath the surface and into the core of a person. Perry considers identity to be a journey, a voyage in pursuit of who we are: “Our identity is an ongoing performance that is changed and adapted by our experiences and circumstances.” This notion interests me. Perry clearly grasps the interchangeability of identity. His documentary sparked my enthusiasm and provoked a question I've been wrestling with ever since: How do I create a portrait that reaches beyond accurate representation to reveal the complexities of an individual identity?

The following sentence starters seem to fit with the style of example 1, above:

I am choosing to focus on… (Artist / art movement) because…/ It astounds me how…/ I find it fascinating that…/ I found myself reflecting upon. / I’m curious to know why…/I hope to. show, share, highlight, discover…

These provide a sound enough framework to begin with, but perhaps lack the descriptive verve of Example 2.

Example 2 uses a more elaborate style that incorporates a creative metaphor (identity as a pearl inside us all) and also a direct quote from the artist. Confident statements provide a greater sense of authority ("this strikes me as absurd", "Perry grasps the interchangeability of identity"), but also - importantly - the writer is not setting themselves up as an absolute expert. There remains a a reflective tone ("a question I've been wrestling with is. ").

Reading, a reoccurring theme in these portraits by Picasso

The meat in the sandwich

With a word limit of 3000 words (and advice to aim for less) there's good reason to be concise. Short and punchy is best. You need to move quickly to the main content of your essay - the meat in the sandwich. And this should certainly give the reader something to chew on. Frankly, on behalf of all teachers who have to digest these servings, the more flavour the better.

- Revealing insights to specific artwork(s) – descriptive writing incorporating lesser-known facts; wider contextual connections; personal insights - perhaps in relation to your own practical work and experiences. But don't dismiss how an artwork makes you feel or impacts upon your senses. (Refer to Threshold Concept #6). Be sensitive to your intuition and honest in accounting this.

- Imaginative leaps and connections – this might include linking an artwork or idea to another work or idea, or perhaps a significant moment in time. Connections might be made between styles, techniques or ideologies; moments of personal, historical or cultural significance can be linked with thoughtful insights or questions. (Refer to Threshold Concept #7).

- Narrowing your focus – when the possibilities seem endless, narrowing your focus might help. For example, if referencing a particular artwork, consider focusing on one of these 4 aspects: TECHNICAL, VISUAL, CONTEXTUAL and CONCEPTUAL. Do you want to provide technical insights (the type of materials used, the technical skills involved etc.), or perhaps a visual analysis is more fitting (of subject matter, composition etc.)? All essays should demonstrate contextual understanding, and reveal concepts and ideas, but this might not be necessary for every artwork referenced. (Refer to Threshold Concept #3).

- Accompanying images/illustrations – Your Personal Study should be accompanied with relevant images/illustrations, but there is no set way to do this. Most students opt to embed these alongside their writing for ease of reference. Alternatively, they might be included as an appendix - a page at the end of the essay. Either way, think carefully about the relevance, order, scale and placement of images, and reference them consistently within your text. You can do this in a couple of ways, e.g:

- “ This technique was very expressive (Figure 1) and. ”

- Your initial reaction–informed by instinct, intuition, emotional response, existing knowledge etc.

This is appropriate when your initial reactions are justified e.g. “I'm intrigued by this because…”; "when I firstencounteredthe work I was taken by surprise because. " But if what follows is a basic and superficial understanding of wider contexts then, well, that might just make your teacher cry. “I’m interested in Cubism because I like how Picasso’s artworks are made up of cube-like shapes”; or “Pop Art appeals because it uses bright colours and film stars”. Whether your teacher cries tears of despair or laughter will depend on your relationship with them, or perhaps their performance management targets. But they won't be tears of joy.

- Based on a deeper understanding/complex grasp of wider contexts – demonstrating a confident stance; justified, informed opinions; an ability to make imaginative connections etc.

Compare these improved examples to the previous tear-inducing responses:“I’m interested in Cubism, particularly how the concept of recording multiple viewpoints evolved through experimenting with - and challenging - traditional methods of depiction. "; “I’m interested in how Pop Art emerged as a response to Abstract Expressionism. It strikes me as a mischievous movement; an antidote to theexcessive chin-holding culture which pervaded galleries at that time…”

- From an alternative perspective –demonstrating an awareness that art is not fixed in meaning but subject to interpretation; that the opinions of others can provide alternative perspectives 0r counter-balance anargument etc.

Placing yourself in someone else’s shoes can demonstrate a deeper awareness of the capacity of art to evoke various opinions and responses. For example, consider the perspective of a feminist, a modernist, or a post-modernist. “Rothko may have set out to provoke a sense of claustrophobia with his Seagram Restaurant commission, but I can imagine a dining capitalist might have been less sensitive to the colour fields on the wall, and more preoccupied with the greenbacks in hand…”

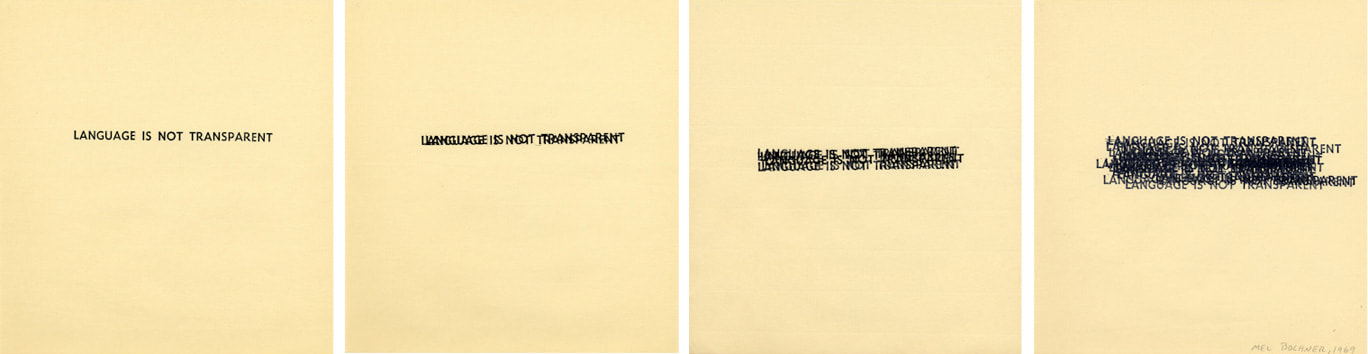

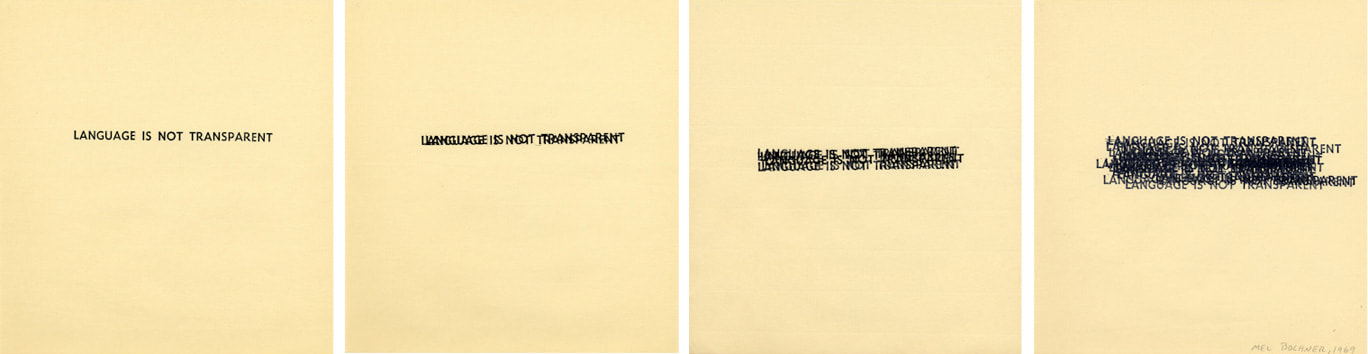

Mel Bochner, LANGUAGE IS NOT TRANSPARENT, 1969

- Revisit the aims or investigative questions set out at the start. You do not need to have definitive answers though. Sensitive and honest reflections, or even new, increasingly complex questions are fine.

- Summarise key thoughts that have arisen from your study.

- Offer reflective, personal opinions on your research, and how this has shaped - or will shape - your own practical work.

- Share thoughts on potential opportunities for future exploration, if given more time.

- Include a short reflection on the process of the study itself – the research and thinking skills that you've developed along the way.

- Author – put the last name first.

- Title – this should be underlined or in quotation marks.

- Publisher - in a book this is usually located on one of the first few pages.

- Date – the date/year the book/article was published.

For websites the format is similar, and the author should be included if known. For example:

Jonathan Jones, 'Feeding Fury', The Guardian (December 20o2), https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2002/dec/07/artsfeatures

- word-processed and double-spaced.

- All imagery should be clearly referenced within the text, as detailed above.

- The bibliography should be on its own page at the end of the essay.

- With an appropriate cover, thoughtfully designed, including the essay title and your name*

- Ring bound with acetate cover and a card back*